Uyghur language - Uyghurche - ئۇيغۇرچە

In this coming Spring semester, I will be taking my first class in the Uyghur language. Uyghur (oo-ee-ghur) is spoken primarily in Xinjiang 'new dominion' (also called Chinese Turkestan) in the northwestern portion of the People's Republic of China (PRC). There are also speakers in neighboring Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan1. Uyghur is a Southeastern Turkic language. It is related to Turkish. (Turkish is spoken in Turkey, while other Turkic languages are spoken across central Asia, including Uyghur, Turkmen, Tatar, Uzbek, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz. Just remember that, while Turkish is a Turkic language, not all Turkic languages are Turkish.) While Uyghur has several million speakers, it is considered a "threatened" language due to the infiltration and imposition of the PRC's primary official language, Mandarin. (This is not unlike the situation here in the US with the imposition of our official language, English, upon Native Americans, for example, whose languages and cultures for the most part, if not already extinct, are close to it.)

Uyghur-speaking region of western China, centered around Kashgar.

The Uyghurs (often erroneously referred to as 'Chinese Muslims' even on such respected US national media as NPR, which should know better!) are one of over 50 ethnic minority groups of the PRC. They have inhabited northwestern China, which includes the Teklimakan Desert (Tarim Basin), since about 900 CE. The famous Silk Road passes through here and it has long been a major crossroads and trade route between West and East. Its inhabitants have included Tocharians (a possible Celtic group who inhabited the region from about 2000 BCE2), Persians, and Mongols as well as Uyghurs. Mummies have been unearthed in the Tarim Basin region buried under desert sands for some 4,000 years that are apparently the well-preserved bodies of the blond and blue-eyed Tocharians (see my prior post on this topic), probably originating in northern Europe. (In fact, many inhabitants of the region still have the light hair and facial features of their Tocharian ancestors.)

Red-haired child of Xinjiang

Uyghur and the other Turkic languages are part of the broader Altaic language family, which includes Turkic, Mongolian, Korean, and possibly Japanese. While Altaic was for a while also believed related to the Uralic languages, including Hungarian and Finnish, but this idea remains controversial. (The inclusion of Japanese under the Altaic umbrella is also still hotly debated.) For me, one of the most intriguing aspects of studying Uyghur is from the historical-comparative linguistic perspective of seeing how the language has borrowed from other languages throughout its history. For example, kitab 'book' and mu'ellim 'teacher' are from Arabic; istakan 'glass' and poyiz 'train' from Russian; dunya 'world' from Persian; much 'pepper' from Sanskrit; pul 'money' possibly from Tocharian (?); and yangyu 'potato' from Chinese. The meanings of these borrowed words occasionally changed when introduced into Uyghur; the Uyghur word lughet 'dictionary' was borrowed from Arabic, in which the word originally meant 'language.' Sometimes two borrowed words compete with each other: tëlëwizor (Russian) and dyanshi (Chinese), both meaning 'television.'

The letters of the (Latin) Uyghur alphabet are: a, e, b, p, t, j, ch, x, d, r, z, zh, s, sh, gh, f, q, k, g, ng, l, m, n, h, o, u, ö, ü, w, ë, i, and y. For English speakers, the hardest sounds to pronounce are the very Scandinavian-like ö and ü, and the three guttural sounds x, gh, and q. Uyghur has been written with three different scripts: Latin-based, Cyrillic-based (as used in Kazakhstan and other Commonwealth of Independent States [CIS] [formerly of the USSR] countries), and a modified Perso-Arabic script (used in writing Farsi, or Persian). The latter has been adopted by the Xinjiang Language and Script Committee (Xinjiang Til-Yëziq Komitëti Tetqiqat Merkizi 2008) as the official transliteration system for Uyghur.

Tarim Basin, Xinjiang

Like other Turkic languages, Uyghur is subject to rules of front-back vowel harmony. For instance, the locative ending -da changes according to the final vowel sound of the noun it is attached to: suda 'at/on the water', atta 'on the horse', mektepte 'at school.' Uyghur is heavily agglutinative, meaning suffixes are added to roots to build up larger words, words that must often be translated by entire sentences in English: oquwatqanimda 'When I was studying...." (Such agglutination, I might add, is also characteristic of many Native American languages, including those of the Algonquian family.) Uyghur, like its Turkic relatives, has a complex modal system, including a system of evidentiality, through which one communicates how they received a certain bit of information: first-hand, through witnessing the event directly oneself, or second-hand, via a second or third party report, which may incorporate the speaker's judgment of the information's reliability or believability. Such systems of evidentiality also occur (surprise, surprise?) in many Native American languages, including Biloxi, as well as in Tibeto-Burman languages.

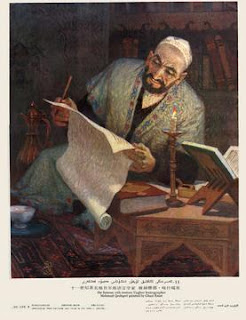

Artist's rendition of Mahmud Kashgari, compiler of the first Uyghur dictionary ca. 1050 CE.

Some Uyghur words English speakers might recognize: chay چاي 'tea' , bazar بازار 'bazaar, market', aral ارالئ 'island' (Aral Sea 'Island Sea'), tansa تانسا 'dance' (Russian), nan نان 'bread' (Indian or Persian nan), salam سالام 'peace' (Arabic), seper ~ sefer سەفەر 'trip/journey' (cf. Swahili 'safari'; Arabic).

1 The ending -stan is a Persian suffix meaning 'place of' and is related to Sanskrit sthāna, Latin status, and English state.

2 Modern anthropologists have generally adopted the abbreviations BCE (Before Common Era) and CE (Common Era) in place of the former BC (Before Christ) and AD (After Death [of Christ]) due to the Christian religious connotations of the latter.

No comments:

Post a Comment